BY NATHAN CRANFORD

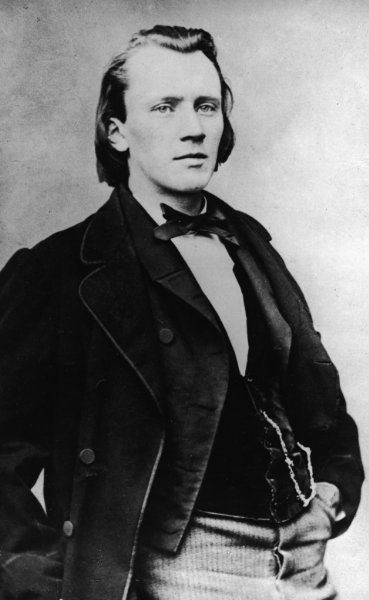

This weekend at the San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson Thomas, along with famed violinist Gil Shaham, will be leading the orchestra in another performance of the works of 19th Century German composer Johannes Brahms. However, whereas last week’s program was a comparative study of progression in German musical conservatism, this week’s program showcases the contentious battle between conservative and progressive elements in the music of German Romanticism.

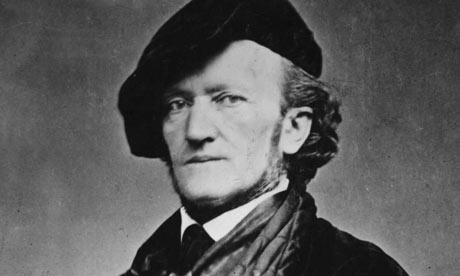

The evening begins with a work by the great German operatic composer Richard Wagner, the “Prelude” to Act III of his famed opera Lohengrin. Familiarity with the opera’s plot is not necessary for an appreciation of the work, which is often performed alone in concert due to its highly exciting and virtuoistic writing for orchestra.

Less than 5 minutes in length, many listeners will find the melodies showcased by the “Prelude” (which are repeated throughout the opera) to be immediately recognizable. Although it’s not being performed by the Symphony this weekend, the end of the “Prelude” flows seamlessly into the even more famous “Bridal Chorus”–a piece of music that has become associated with the bride walking down the aisle at weddings throughout the world.

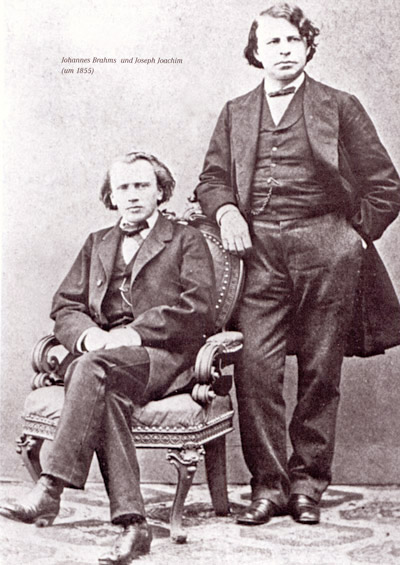

The “Prelude” acts as an almost ironic beginning to an evening dominated by Wagner’s musical arch-nemesis, Johannes Brahms. His Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 77 was written for his close friend and confidante Joseph Joachim, to whom it is also dedicated. The work comes almost two decades after the two took on the cause of conservative musical values against the progressive forces of German music led by the pianist/composer Franz Liszt and his son-in-law Richard Wagner in what is now referred to as “War of the Romantics.” What the war really boiled down to was the importance of absolute music (music independent from all other artistic influence) over program music (music that is based upon or related to another work of art). The war did not end well for Brahms, whose conservative “manifesto,” co-authored by Joachim, was only signed by 20 or so other musicians upon publication. This loss of influence in the German musical arena subordinated Brahms’ sway over musical matters to the progressives, and (in combination with several other unhappy events) molded him into a rather bitter and reclusive man as a result.

Aside from the politics that marked their early friendship, Brahms’ Violin Concerto was composed as a vehicle for Joachim to showcase his tremendous skill in concert throughout Europe. The concerto’s pomp and grandeur did much to bring out the untapped potential of the instrument, and was a technical challenge for even Joachim to master. Despite the work’s mixed critical reception at the time of its premier, Brahms’ Violin Concerto is now almost universally considered to be one of the greatest German works of its kind, in addition to being a staple of the concert violinist’s repertoire.

The Symphony will close out the evening with an orchestral transcription of Brahms’ First Piano Quartet in G Minor by 20th Century German composer Arnold Schoenberg. Before completely pushing German music forward into ultra-progressive territory, Schoenberg stood as one of the more respected students of both Brahms’ and Wagner’s contributions to German music. Although it is easy to assume that Brahms would detest Schoenberg’s orchestral treatment of his quartet, which the latter disliked due to the piano’s tendency to drown out the strings, the transcription is an interesting reimagining of what the work might have sounded like under the “flashy” influence of Richard Wagner’s programmatic writing for orchestra. Although the quartet was originally conceived by Brahms as absolute music, Schoenberg’s use of non-traditional instruments (for Brahms), such as the xylophone, cymbals and tambourines, gives the work an aura of being based upon a particularly exciting program to be imagined by the listener.

All in all, these three works showcase the connections both Wagner and Brahms shared in their ability to create music highly charged with excitement and virtuosity. Although both composers were considered to be enemies during Germany’s highly charged musical climate in the mid to late 19th Century, the works performed this weekend show that the musical bonds that tied these composers together were often stronger than the differences in opinion that separated them. Schoenberg’s masterful transcription of Brahms’ early quartet for piano and strings (composed during the “War of the Romantics”) proves that the techniques of both composers could be fruitfully synthesized to create a showpiece for orchestra that gives one the impression of being programmatic while remaining absolute in its autonomous musicality.

RELATED LINKS

San Francisco Symphony Official Website

Program and Tickets for This Event

Let us know what you think! Follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook to give us a shout. You can also stay on top of exciting events from around the world by downloading the eventseeker app for iPhone, Android or Windows.