BY NATHAN CRANFORD

This weekend at Davies Hall, music director Michael Tilson Thomas returns to the podium for a performance that highlights some of the more radical entries in the modern repertoire by composers of American descent.

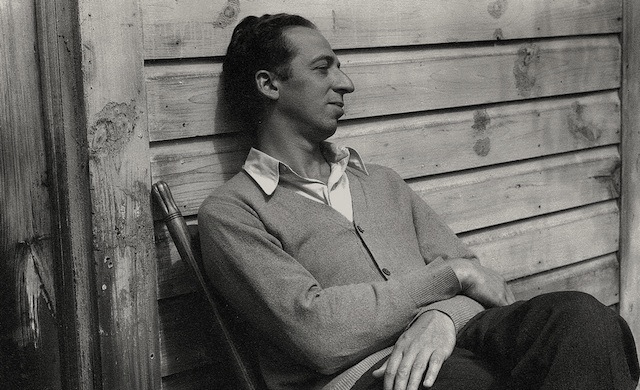

The evening begins with a work by one of the more renowned American composers of the 20th Century, Aaron Copland. Copland was one of the first American composers to join the ranks of such Nationalist composers as Edvard Grieg, Antonin Dvorak and Pyotr Tchaikovsky for his ability to elevate folk idioms (American, in his case) to the level of “serious” concert music. In addition to shattering many of the world’s stereotypes concerning American music, Copland’s most revered works are actually those that celebrate the splendor of the expansive American frontier and populist spirit, such as Rodeo, Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid, and the ubiquitous Fanfare for the Common Man. In fact, the composer’s Third Symphony was deemed by close friend and colleague Leonard Bernstein as “the epitome of a decades-long search by many composers for a distinctly American music.”

The work being showcased by the San Francisco Symphony this weekend, Copland’s Orchestral Variations, was produced in 1957 by the composer to be performed by the Louisville Symphony Orchestra. The piece is actually an orchestral transcription of a much earlier work for piano entitled Piano Variations, which was written in 1930 during what musicologists refer to as Copland’s “second period,” or the period in which the composer focused on more abstract and experimental elements of music that were in vogue during the first half of the 20th Century. Aside from its relative lack of renown, the Piano Variations are generally considered to be one of Copland’s most important works for the instrument, and act as a sort of “thesis” of sorts that proved the composer’s mastery of more serious forms of “absolute” music (or music that has no specific program or literary subtext to go along with it). The work is a significant departure from the lush, distinctly American soundscapes conjured by much of Copland’s later music, and might come across as a bit too cerebral and cold for the average listener. However, as an orchestral arrangement, the Variations gain some additional sonic excitement and tone color that were purposefully avoided when Copland composed the much sparser piano original.

The work being showcased by the San Francisco Symphony this weekend, Copland’s Orchestral Variations, was produced in 1957 by the composer to be performed by the Louisville Symphony Orchestra. The piece is actually an orchestral transcription of a much earlier work for piano entitled Piano Variations, which was written in 1930 during what musicologists refer to as Copland’s “second period,” or the period in which the composer focused on more abstract and experimental elements of music that were in vogue during the first half of the 20th Century. Aside from its relative lack of renown, the Piano Variations are generally considered to be one of Copland’s most important works for the instrument, and act as a sort of “thesis” of sorts that proved the composer’s mastery of more serious forms of “absolute” music (or music that has no specific program or literary subtext to go along with it). The work is a significant departure from the lush, distinctly American soundscapes conjured by much of Copland’s later music, and might come across as a bit too cerebral and cold for the average listener. However, as an orchestral arrangement, the Variations gain some additional sonic excitement and tone color that were purposefully avoided when Copland composed the much sparser piano original.

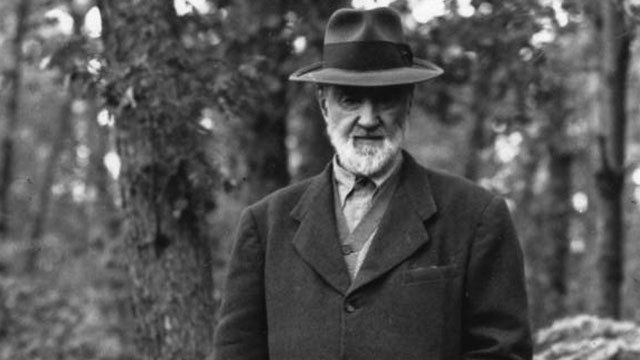

Following the Copland, Michael Tilson Thomas will be leading the percussion section and organ in the Concerto for Organ with Percussion Orchestra by the Bay Area’s own Lou Harrison. The work was composed in 1972 for a close friend of the composer, Philip Simpson, who taught organ at San Jose State University and later premiered the work with the university orchestra. The work is indeed expansive in scope, honing in on an interesting dichotomy between the abstract and often biting percussion, and the sonorous pipe organ. Sections of the work where equally tempered percussion instruments such as the piano and glockenspiel are put to use serve as a sort of dream-like tonal backdrop to the organ in certain places. Overall, the work is very complex and ambitious in its imagination, and I am sure this weekend’s performance will do Harrison’s work much justice.

Following the Copland, Michael Tilson Thomas will be leading the percussion section and organ in the Concerto for Organ with Percussion Orchestra by the Bay Area’s own Lou Harrison. The work was composed in 1972 for a close friend of the composer, Philip Simpson, who taught organ at San Jose State University and later premiered the work with the university orchestra. The work is indeed expansive in scope, honing in on an interesting dichotomy between the abstract and often biting percussion, and the sonorous pipe organ. Sections of the work where equally tempered percussion instruments such as the piano and glockenspiel are put to use serve as a sort of dream-like tonal backdrop to the organ in certain places. Overall, the work is very complex and ambitious in its imagination, and I am sure this weekend’s performance will do Harrison’s work much justice.

The final work being showcased this weekend by the SFS is also an orchestral transcription of a work originally written for piano: Charles Ives’ A Concord Symphony, transcribed and renamed by Henry Brant from Ives’ Piano Sonata No. 2, also known as the Concord Sonata. Brant’s orchestral arrangement does wonders in bringing the highly experimental harmonies of the Piano Sonata (a pianist actually needs to use his or her fist or a piece of wood to depress “clusters” of notes on the piano when playing) to life in an orchestral setting. This is considered by many to be one of Ives’ greatest works, and serves as a magnum opus of sorts that fully encompasses the composer’s experimental style. Chock full of polytonality and polyrhythms, one of Ives’ more well-known experiments was to have two or more quotations from familiar pieces of music played simultaneously and in different keys–creating a sort of mash-up of sorts that does more to tire than to inspire the ear. However, as fatiguing as the Symphony might be to the listener, it is truly a testament to the experimental freedom American composers such as Charles Ives had at the turn of the 20th Century, and how brave and forward-thinking the composer truly was before the “avant-garde” started being explored in Europe several decades later.

Although I cringe when I see the composers on this weekend’s program so tackily described as “American Mavericks,” I must agree with its connotation. The three composers showcased this weekend not only strove to break the so-called rules of music in many respects, but did much to push forward the possibilities of music composition and to raise awareness of American music and its import on the world stage. Michael Tilson Thomas was right to schedule this performance to take place upon his return from vacation, as few conductors have done more than he has to bring to light the great music of our shared American heritage.

RELATED LINKS

San Francisco Symphony Official Website

Follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook to give us a shout. You can also stay on top of exciting events from around the world by downloading the eventseeker app for iPhone, Android or Windows.