BY NATHAN CRANFORD

This weekend at the San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson Thomas will be leading the orchestra in performances of three very disparate pieces of German music: Ich bin ein rechter Weinstock by Heinrich Schütz, Arnold Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra, and the evening’s centerpiece, Johannes Brahms’ German Requiem.

The first piece, Ich bin ein rechter Weinstock (I’m the Only True Vine) is a choral work by 17th-century German composer Heinrich Schütz that is based on Bible verses from John 15:1-5. The passages are believed to be the words of Jesus himself as he explains to his disciples that he is the one true vine and his followers are its barren branches that will one day bear fruit. Religious connotations aside, Schütz’s work is considered to be an exemplary example of the composer’s mastery of his craft and his meticulous adherence to the established music fundamentals of the time. The work is representative of Schütz’s strict musical conservatism, which set him in dialectical opposition to many of his contemporaries who sought to push the boundaries of musical expression through experimentation.

Almost three centuries later in Germany, Arnold Schoenberg would rise to become the spiritual successor of many of the great stalwarts of German music, of whom Schütz, Bach, Mozart and Brahms are just a few. However, unlike his predecessors, Schoenberg’s commitment to music from a strictly academic perspective is often confused by the fact that his music is almost completely atonal. One of his most famous works, the Five Pieces for Orchestra, Opus 16 (1909) marks the beginning of Schoenberg’s quest to free German music from the trappings of a tonal system that had pervaded Western music since its beginnings.

The work is not easy to listen to or understand, and the extensive program that accompanies each movement betrays the composer’s anxiety that his music would be written off by audiences and critics as Expressionist “noise.” Schoenberg’s deep, almost ascetic dedication to the music fundamentals of his forefathers was often at odds with a passionate desire to become the next great innovative composer in the German musical tradition. Written during a very dark period in the composer’s life, the Five Pieces for Orchestra represents a tipping point in Schoenberg’s career, and stands as one of his last pieces to still (barely) adhere to conservative musical tenets.

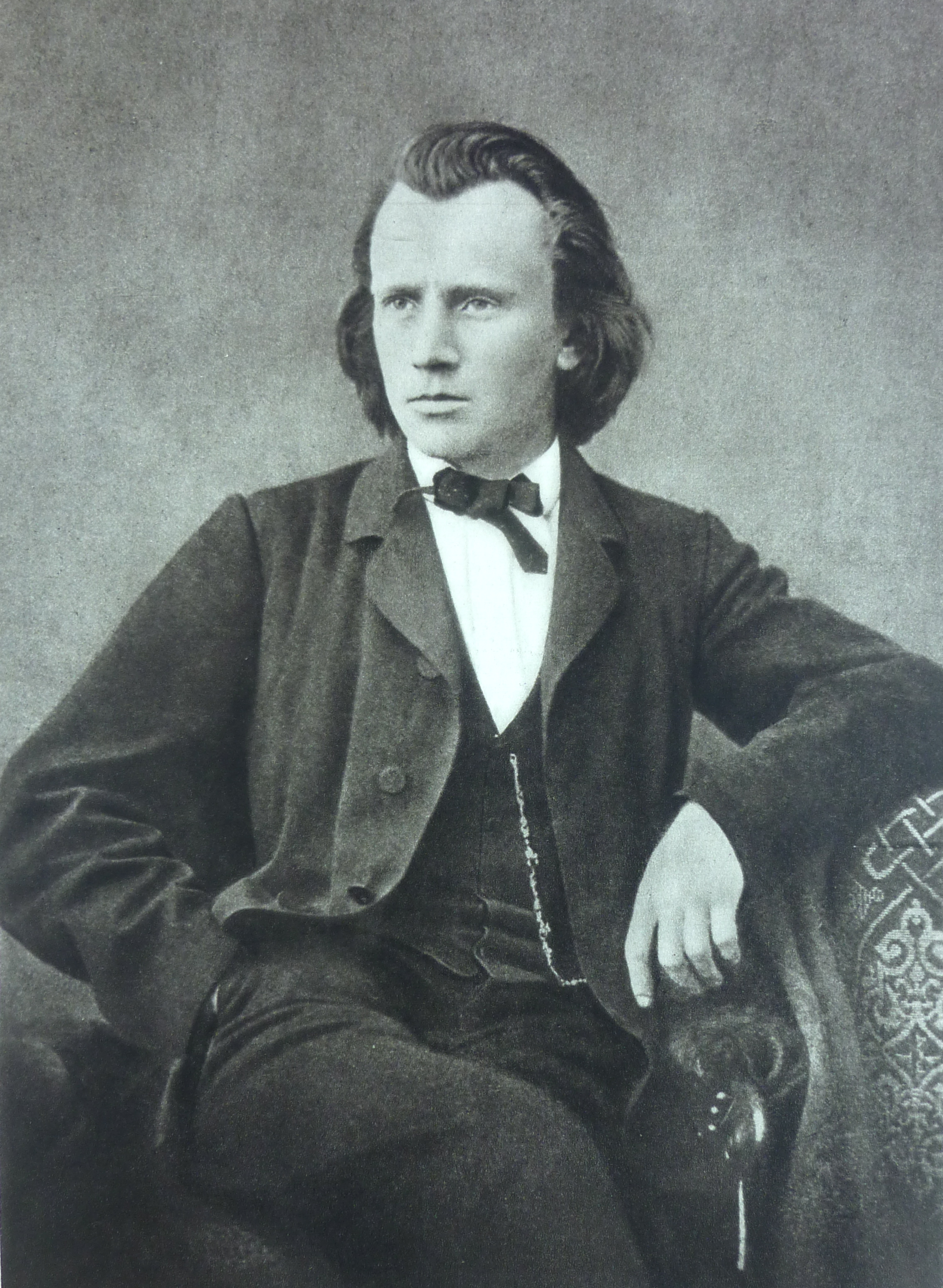

The Symphony will end its program with a performance of Johannes Brahms’ magnum opus, the majestic A German Requiem, to the Words of the Holy Scriptures, Opus 45. Written between 1865 and 1868, the Requiem relates to the first work on the program in that it is based on the Lutheran tradition of using German instead of Latin for sacred music. The work relates to Schoenberg’s Opus 16 in the sense that it was written during a particularly tragic period of Brahms’ life (his dear friend and mentor Robert Schumann as well as his mother had recently died) and stands as one of the composer’s most expressive and spiritually gratifying works. Moreover, it has an almost monolithic place in the standard choral repertoire and is considered by many to be Brahms’ greatest work.

Although the connections these three works have might not be readily apparent to the average listener, the connections are indeed there. The music showcased by the San Francisco Symphony this weekend is considered to be quintessentially German, in addition to being written by three of the more conservative defenders of the German musical tradition. Heinrich Schütz’s Ich bin ein rechter Weinstock sets a base line for the evening as a representation of Germany’s conservative musical roots, later expanded and built upon by the epoch of J. S. Bach. Arnold Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra sits at the opposite end of the spectrum as the dark expression of a tradition’s final gasp before Germany’s dominance over Western music came to a cold, bitter and violent end. At the conclusion of the program, however, one is reassured by Brahms’ glorious German Requiem, which, as a near-perfect synthesis of the Apollonian and the Dionysian in German music, comforts the listener by proving that change and rebirth is never truly as bad as it seems.

RELATED LINKS

San Francisco Symphony Official Website

Program and Tickets for This Event

Let us know what you think! Follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook to give us a shout. You can also stay on top of exciting events from around the world by downloading the eventseeker app for iPhone, Android or Windows.