This fall and winter, the museum world in Southern California will be dominated by Pacific Standard Time–a gargantuan initiative by the Getty meant to celebrate the postwar art of the region. Not long ago I headed down south to check it out. My first stop was the Long Beach Museum of Art, which decided to approach the theme quite unconventionally. “Exchange and Evolution” explores not Californian art, but the history of the museum as a hub for video practitioners from all over the world.

This focus absolutely makes sense when you think about how adventurous the LBMA’s video programming was in the designated period (1974 to 1999). The history of how it all started has a poignant parallel to the site itself. From the museum lawn you can see several peculiar islands with extremely tall, skinny palm trees and modernist structures that glow in psychedelic colors in the dark; this spectacle camouflages the reality of big business – the islands are platforms where a few oil companies drill away. It is well known that art sometimes performs a function similar to those “buildings” and palm trees, serving as “decor” for the processes of gentrification. That’s what happens to some rundown areas: first the artists arrive, then the rich (we in San Francisco will no doubt witness a surge in art support in Bayview-Hunters Point, with the redevelopment of that neighborhood). Indeed, in the ’70s, the Long Beach city authorities’ interest in “innovative” practices like video art stemmed from their determination to revitalize the downtown area. In the end, the funding that the LBMA received was meager (culture is never the main beneficiary of gentrification), and the promised new building by starchitect I. M. Pei didn’t materialize. However, the video program was kick-started, and fueled by the tremendous enthusiasm of the museum employees, succeeded in making the institution an important node in the worldwide arts network.

In those years of optimism about video as a tool of democracy, the LBMA sought no less than to reenvision the role of the museum–as Gloria Sutton writes in the exhibition catalogue, it “suggested a model of the art museum as a site of production and broadcast alongside its more orthodox job as repository for cultural patrimony.”¹ The museum opened a post-production studio for video artists in its attic (the facility later moved into an annex in a former police station) and planned to conquer cable television with its own channel–which, again, failed to materialize, although some works did manage to get shown on TV. And of course, the LBMA provided space for thousands of time-based pieces, its tentacles spreading to faraway places like Japan and Eastern Europe and un-lofty genres such as music video. “Exchange + Evolution” and its accompanying screening program feature artists (Marina Abramović, Nam June Paik, Bill Viola, etc.) that are essential names for anyone who wants to understand contemporary art. The works in the exhibition are uniformly strong, and they reveal some of the major preoccupations of art in the past few decades. Experiments with technology, exploration of identity, feminism, the problem of how to portray the culturally different “Other,” critique of the art system–it’s all there.

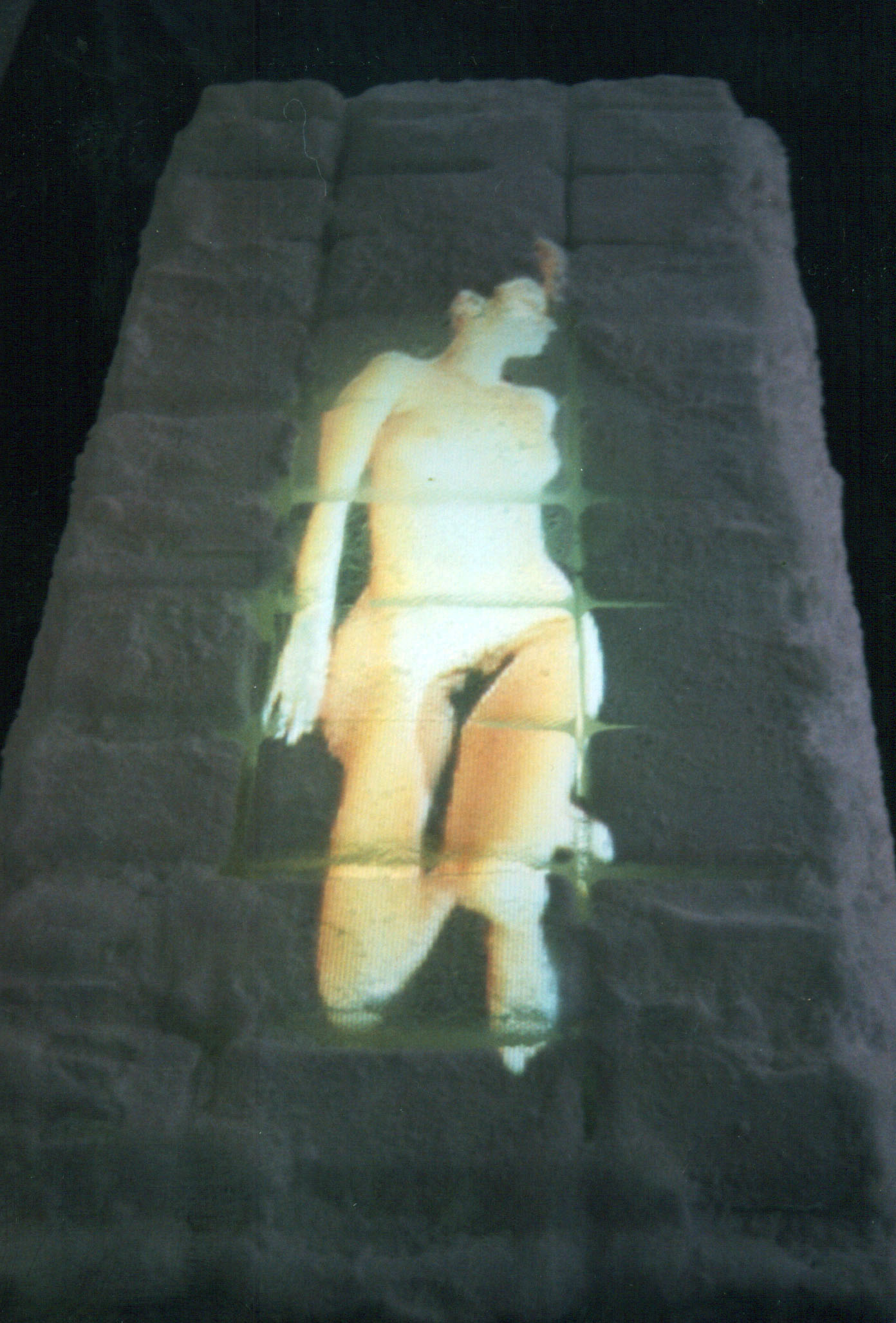

Sanja Iveković Croatian, b. 1949 Frozen Images, 1992 Single‐channel color video installation with sound, 60 min. Wood frame: 78.7 x 39.4 in.; and thirty‐six blocks of dry ice Courtesy the artist and Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Here are some of my event highlights:

At the start of the exhibition I was mesmerized by the work “Doors” (1981) by Nan Hoover, who with the staggering economy of imagery (just a woman in black, head unseen, opening/closing a white door and walking past) created an unsettling, ghostly, almost abstract presence. The sound of heavy breathing bled through the wall; that was the soundtrack of the work in the next room–an installation by the great Croatian artist Sanja Iveković (pictured above). In “Frozen Images” (1992) a video of a sleeping nude woman is projected on a bed of dry ice. At first I did not “feel” this work, but coming back the next day, I found that most of the ice had evaporated and the figure was totally deformed. Essentially depending on time, Iveković’s piece is a condemnation of violence towards women and their invisibility in the grand narrative of history. Another powerful feminist work is “Kiyoko’s Situation” (1989) by Mako Idemitsu, which borrowed the lowly form of the TV melodrama (combined with her own device of a “screen on a screen,” which shows the inner world of a character) to tell the horrible story of a female artist stifling in a patriarchal Japanese society.

Antoni Muntadas‘s huge eight-monitor installation “Between the Frames: The Forum” (1983-93) is a sly commentary on the Reagan-era art world mores. In that work, interviews with various art world participants make up the soundtrack to seemingly out-of-place visual material. The juxtaposition of art collectors’ words about “risk-taking” and “determining value” with a video of frenzied traders on a stock exchange was so smart that I laughed out loud.

Bjørn Melhus Norwegian, b. Germany, 1966 Again and Again (The Borderer), 1998 Eight‐channel color video installation with sound, 6 min. Dimensions variable Collection Kunsthalle Bremen—Der Kunstverein, Bremen, Germany

A very popular piece among the museum visitors, “Again and Again (The Borderer)” (1998) by Bjørn Melhus casts the artist as an androgynous, childlike being who constantly multiplies and talks in a female voice (Melhus appropriated phrases from TV shopping programs). The piece suggests the total malleability and undefinability of identity in a “post-everything” world.

The museum’s Ocean View gallery is given over to one-channel works–one video is screened continuously for a few days (currently they’re showing Robert Cahen’s “Hong Kong Story”). When I was there, I saw “Black Celebration (A Rebellion Against Commodity)” (1988) by Tony Cokes. The artist couples footage of the Watts Riots with a ferocious soundtrack by Industrial band Skinny Puppy. I found it extremely interesting how the work explored the “romanticization” of civil disobedience–after a prolonged exposure to such adrenaline-pumping audio and video you just itch to grab a Molotov cocktail and run out into the street to burn stuff. But since it was the opening, I went to grab some wine.

The last work I want to tell you about is by Ko Nakajima. It’s a (deceptively) simple two-channel installation cooked out of home movie footage. The title is “My life” (the years of creation are 1974-92). On the left screen we see the funeral of the artist’s mother, while the right one shows moments in the early life of Nakajima’s daughter. What’s curious is that the moments of life (and death) always unravel in the presence of other people; somebody is always constantly talking. In Nakajima’s video, everything happens within society, within a community. The work shows the mother and the daughter, but we are always aware that we are looking at them through the artist’s eyes. He makes a portrait of himself through his family, which makes “My life” a powerful work about human connection.

You can check out the whole program of the exhibition on the LBMA website. The show will run until February 12th, and you won’t regret it if you go.

¹Gloria Sutton, Playback: Reconsidering the Long Beach Museum of Art as a Media Art Center. Exchange and Evolution exhibition catalogue, p. 125.

RELATED LINKS

Long Beach Museum of Art Official Website

Let us know what you think! Follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook to give us a shout. You can also stay on top of exciting events from around the world by downloading the eventseeker app for iPhone, Android or Windows.