BY EVENTSEEKER STAFF

Strangely enough, at the press preview of the “Pissarro’s People” exhibition at the Legion of Honor, every time the museum director said the painter’s last name, I kept hearing “Bizarro.” That would be an ill-fitting name for the Impressionist master, since there is nothing bizarre in his oeuvre. In fact, he made a point of being very down-to-earth. Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) is known primarily for his rural landscapes. This exhibition, which focuses on images of people, is replete with similarly prosaic subject matter: day-to-day activities of the painter’s family members, laborers in the fields, traders at village markets. Nowadays, when so much work shown in museums and galleries aims to excite your mind and senses, such un-spectacular themes only hold allure for most museum-goers when coupled with the style of a true master. Pissarro’s paintings offer a lot in terms of sensual delight–I particularly prefer his pointillism-influenced works, which seem to extend far beyond the boundaries of the canvas and envelop the viewer. But what is more remarkable is the thinking behind the art. New research by scholar and the exhibition catalog author Richard R. Brettell shows that in all of his art endeavors, Pissarro was guided by anarchist ideas.

Camille Pissarro Apple Harvest, 1888 Oil on canvas 24 x 29 1/8 in. (61 x 74 cm) Dallas Museum of Art, Munger Fund, 1955.17.M. Photo provided by Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Pissarro’s anarchic world is neither chaotic nor governed by dog-eat-dog individualism. He imagined an “anarchic order” in which people would peacefully coexist and cooperate without any kind of imposed authority, and treat each other as equals. Concerning that last point about equality, it is important to note that Pissarro had an unconventional upbringing: he was born and raised on the Caribbean island of St. Thomas, where he and his siblings (unlike many other white children) attended the same school as the Afro-Caribbean kids. This probably accounted for his exceptional (for the 19th Century) racial acceptance. He was also tremendously respectful of women and the lower classes, portraying maids and farm workers in a dignified way. In fact, manual labor was not completely alien for the Pissarro family, since his wife Julie, whom he met after moving to France, had worked as a servant for the painter’s mother.

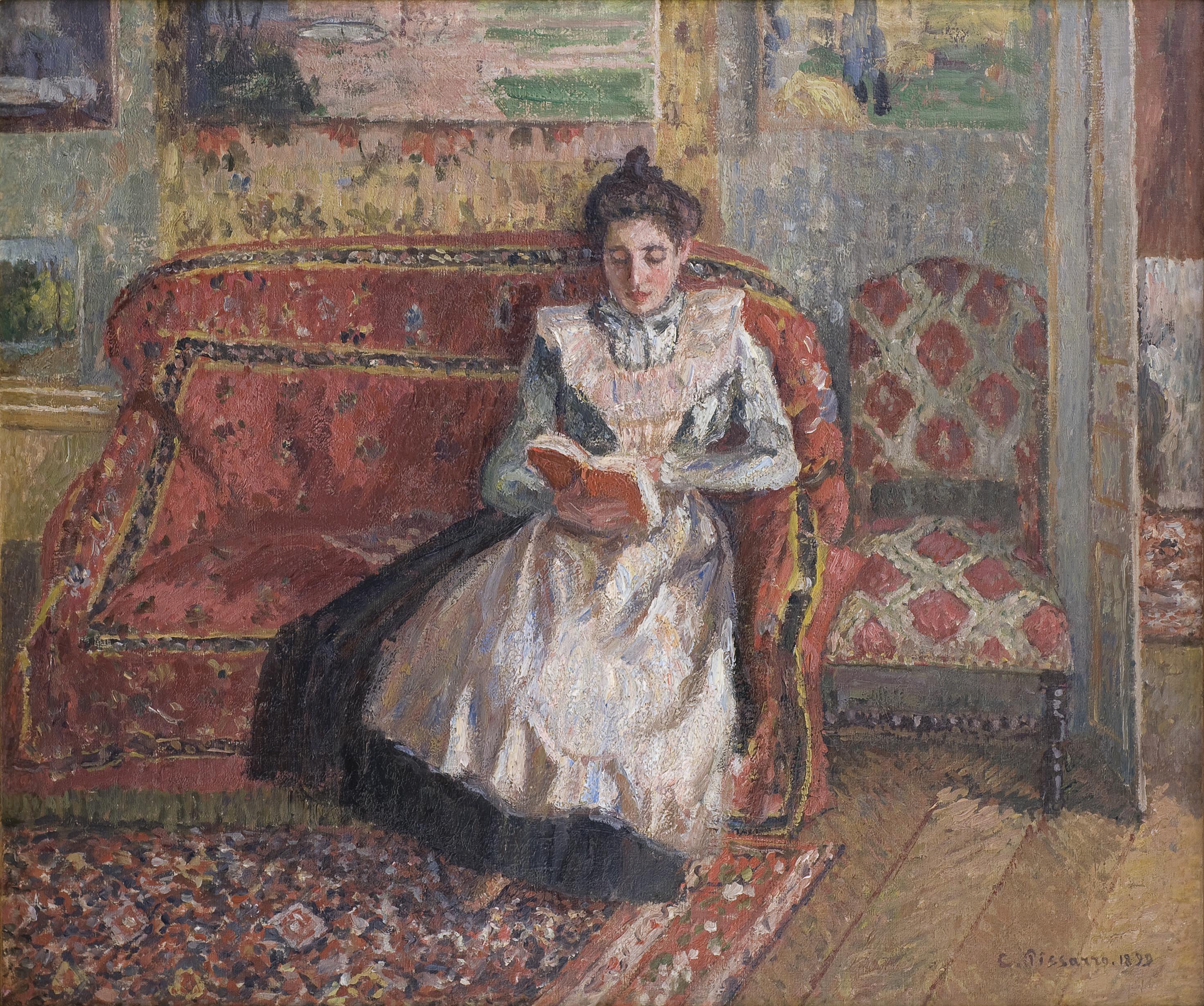

Camille Pissarro Jeanne Pissarro, Called Cocotte, Reading, 1899 Oil on canvas 22 x 26 3/8 in. (56 x 67 cm) Collection of Ann and Gordon Getty. Photo provided by Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Pissarro and Julie had eight children, portraits of whom abound in the show. The artist was a liberal father, which is in line with his non-authoritarian principles: a telling example is how he allowed his son Georges (portrayed in Child with Drum in the exhibit) to keep his hair long after he turned five, a pretty non-conformist thing for a strict bourgeois society. With Pissarro’s friends visiting all the time and the family house abuzz with lively discussions, it was perhaps inevitable that at least some of the children would be inspired to follow their father’s footsteps. Indeed, four of Pissarro’s sons became artists. Some of his works show his children working on paintings; in others they are pictured with books that have red covers, which leaves very little doubt that they contain anarchist and socialist ideas. Pissarro was preoccupied with fostering strong, independent opinions in his kids, and instilling social consciousness in them. Those efforts were actually not limited to his own offspring, as Pissarro once presented his nieces a book of gorgeous drawings called Les Turpitides Sociales, in which he bashed capitalism by depicting various social ills. Les Turpitudes Sociales was his only overtly critical work, but that does not mean that his other works do not have political underpinnings–they were actually the truest representation of his political beliefs. It has been remarked that Pissarro’s rural paintings show the world in a state of anarchy–a world without borders or fences, where healthy and happy men and women work together and rest abundantly without any pressure. But as a true anarchist, the painter also believed in progress, and wasn’t against the division of labor and modern forms of work.

What was lacking in the exhibition? The paintings, drawings and prints on view, as well as the catalog and the explications, are crowded with various characters, but we do not hear their voices–we only hear that of Pissarro. Perhaps it would be naive to expect something other than a conventional presentation of the artist as the lone genius looming over everybody else, but one can dream. It would be great if the curators decided to show us his children’s works (at least reproductions of them, I certainly wouldn’t mind), photographs, ephemera, etc. to make the exhibition lively and messy. After all, the theme of the show offered a great chance for the exhibitors to experiment, to try to apply anarchist ideas to the form of the exhibition itself, to present the painter as first and foremost one among equals. Works by other people (other artists who adhered to the principles of anarchism) are present only in the room where Les Turpitudes Sociales is exhibited, and are very helpful in terms of providing context for his work. The other galleries are impeccably neat, but one cannot escape the feeling that as the lone star, Pissarro seems quite lonely.

RELATED LINKS

Legion of Honor Official Website

Let us know what you think! Follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook to give us a shout. You can also stay on top of exciting events from around the world by downloading the eventseeker app for iPhone, Android or Windows.