I’ve diligently walked through the “Man as Object” show, but I still don’t think I fully understood what the curators meant by “objectifying men.” Male artists have created sexualized depictions of women’s bodies for centuries, and now, as the statement goes, it’s time for ladies to do the same with men. And indeed, images of naked dudes (and just male sex organs) abound in the exhibition, so as to overwhelm everything else.

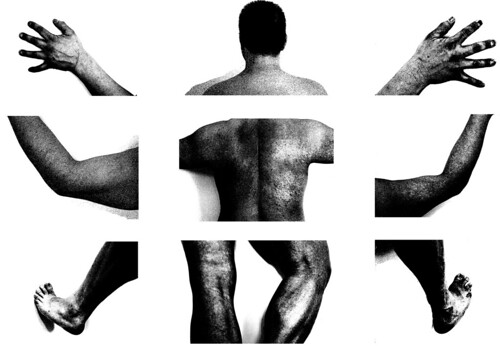

Janice Nesser. Climbing Out of the White. 2008. Inkjet print, plexiglass. 4.5 x 6 feet. Provided by SOMArts.

What you learn at this show is that there are a myriad of ways to depict a naked man. You can make a magazine-worthy tasteful nude with an Apollonic male model. Or tenderly look at your far-from-“perfect” life companion and think: “You are completely unattractive according to today’s standards, but I still love you.” Or poke fun at creeps. Or fetishize tattoos, cowboy hats, muscles and other such vacuous symbols of “masculinity.” Or remind everyone that sexual identity is fluid. If the goal of the organizers was to gleefully inform everyone that “Yay, nude boys can serve as decor, too!” or celebrate female/transgender sexual desires in the spirit of sex positivity, then the exhibition can be considered successful. But my companions and I were left with a feeling that some very important avenues were left unexplored. In general, this exhibit’s particular treatment of the “man as object” theme made that theme seem less compelling than it actually is.

The thing is, the curators (Karen Gutfreund and Priscilla Otani, with Tanya Augsburg) were not completely free to choose which pieces were exhibited, as it was, I assume, a juried show and the majority of the works were chosen from what was sent by artists who competed to be displayed. So it looks like the curators were stuck with what they received and had to combine those competition pieces with other contemporary and historical works. That provided for strange juxtapositions, since works that clearly celebrated the male form were neighbored with pieces such as Orlan’s “The Origin of War” (NSFW!), a critique of patriarchy and male domination where the male sex organ is first and foremost a symbol. The only common thing between those two types of works is their sexual explicitness. And so it goes. Paradoxically, the exhibition overall surprised me as not critical enough, even not feminist enough. Let me explain.

“Object” is a loaded word. Making someone an object means putting him in a somewhat uncomfortable position, where a person loses part of his individuality and becomes the projection of someone else’s fantasies. But men and women objectify each other in very different ways (thank you Lucia Chung, who was the first of us to point it out). “…As the male viewer encounters the male nude, he is required like many women before him to turn the mirror on himself and secondly to feel the powerlessness of being owned and objectified,” goes the curatorial statement. Hmmmmmmm, are we the only ones who think that won’t happen in most cases? While women are pressured by the patriarchal society to be primarily beautiful and sexually attractive, men are pressured to be successful. And don’t think that’s only true for less “liberated” countries where a woman becomes a pariah if she hasn’t found a husband by the age of 25, and a man ceases to be “a real man” if his wife earns more than him. Studies have shown that in America women consider an average guy more handsome if he has an expensive car. Most women have absolutely no qualms about being objectified, and do not ever feel “powerless” in the presence of a female nude, while most men (and in “democratic” societies, more and more women) gladly participate in the game of success – the goal of a feminist exhibition preoccupied with “gaze” is to reformulate these attitudes as a problem and place them in the broad context of patriarchy.

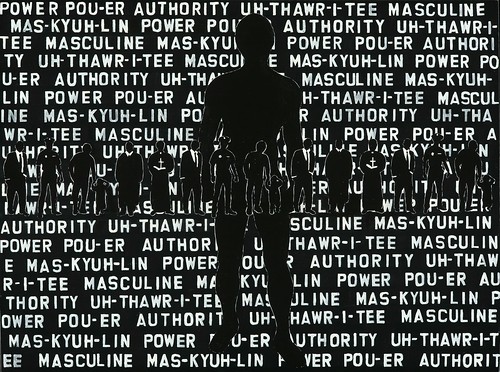

Karen Gutfreund. Power Authority Masculine. 2011. Mixed media on canvas. 30 x 40 inches. Provided by SOMArts.

There was a piece in the exhibition that exemplified what I mean. Interestingly enough, it was one of the few works where a penis wasn’t featured (not that I’m against sexual explicitness in art, mind you). I’m talking about a photograph by Jeanette May, which depicts a serious young man standing in a nice middle-class kitchen, buttoning up his shirt, as if preparing to go to his office. On the right there is a quotation, taken from Lélia by George Sand, where the eponymous heroine describes a man with “the most handsome profile that antique sculpture has ever reproduced.” We read that and wonder: what is the text doing here? The guy is fairly ordinary-looking… Maybe he has some equivalent of a handsome profile, like a good car or a promising career? But wait: on the table there is a girly-pink greeting card with money in it–does that mean he’s a prostitute? Doesn’t look that way… Maybe a prostitute hired to play the role of an upwardly mobile man? Or is his being upwardly mobile just an illusion–is the money from his sugar mommy? Or, does that money signify that his lady is financially dependent on him? Read the passage further, and you’ll see that Lélia, so impressed by the man’s beauty in the beginning, ultimately dismisses that impression as a throwaway: “…she paused for five minutes to observe him as a prodigy. Then she thought of something else.” This sly work definitely makes us think that the man is utterly objectified here–he is stripped of all the power that career success gives him, because the woman is either blatantly using him or is not impressed by what he thinks are his most attractive features. Hence the guy’s look. He’s unsure of himself and wants her approval. Such works, I think, do better to deconstruct and deflate patriarchal mores than artful repackaging of boys as pretty, soulless pieces of meat. We’ve seen that in advertising and boyband music videos – only without the boy parts.

Xian Mei Qlu. Ophelia. 2011. Photograph on plexiglass. 44 x 66 inches. Provided by SOMArts.

You can see the exhibition at SOMArts until November 30. The closing reception will feature the screening of the film Fuse by Carolee Schneemann, as well as a panel discussion “Looking at Men: Then & Now” with the participation of Schneemann, Tanya Augsburg, Annie Sprinkle and Melissa P. Wolf. The event will be free of charge. “Man as Object”‘s next stop will be the Kinsey Institute Gallery at the Indiana University (from April 13 to June 29, 2012).

RELATED LINKS

Let us know what you think! Follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook to give us a shout. You can also stay on top of exciting events from around the world by downloading the eventseeker app for iPhone, Android or Windows.